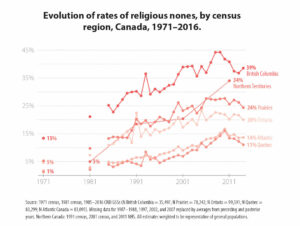

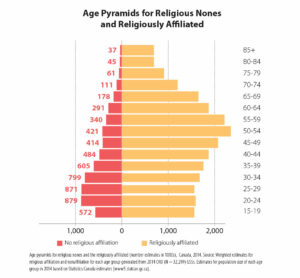

“Religious nones”—those who say they have no religion—are the fastest growing “religious group” in Canada, along with many other modern Western nations. Religious nones currently comprise approximately one-quarter of the Canadian adult population and one-third of Canada’s young people. As you might imagine, regional variations exist. Nearly 40% of those in British Columbia say they have no religion, followed by 34% in the Northern Territories, one-quarter in the Prairies (led by Alberta), one-fifth of those in Ontario, 14% in the Maritimes, and 11% in Quebec.

How do you react to this data? What is the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the phrase “religious nones?” What do you know about religious nones? Do you generally have positive or negative perceptions or experiences of religious nones? How does your church talk, implicitly or explicitly, about religious nones? What is your personal or collective theological response to and engagement with religious nones?

I recently co-authored a book on religious nones with Dr. Sarah Wilkins-Laflamme (University of Waterloo) for New York University Press—None of the Above: Nonreligious Identity in the US and Canada. In our book we explore who religious nones are, why and where they are growing, and what impact they are having on today’s societal and political trends. I am interested in this topic both as a sociologist of religion and as someone deeply committed to my Christian faith and the local church. As a social scientist, I maintain that data matters and tells us something about social reality; data helps to dispel misconceptions and myths that people hold which are not, in fact, true. And then, theologically and practically, I wonder what the growth of religious nones means for evangelical Christians and congregations especially, with their value for evangelism.

To provide a snapshot of religious nones in Canada, here are seven data-driven findings among many others in our research…

1. Most religious nones were raised in Christian homes, however, more and more religious nones are being raised in nonreligious homes altogether. Sociologists call this irreligious or nonreligious socialization. In the years ahead we should anticipate a growth in religious nones with no religious upbringing or exposure.

2. Opposition to exclusive religious beliefs and practices as well as the strong fusion between the Christian Right and Conservative politics are leading reasons, among others, for why many have set aside their religious affiliation and involvement.

3. There is relatively little social stigma associated with saying that one has no religion in Canada today. The same is not true in the United States, particularly in evangelical stronghold states, where religious nones fear “coming out” to their family, friends, neighbours, and coworkers.

4. Not all, or even most, religious nones are atheists, nor are most “spiritual but not religious.” Religious nones are a diverse population, with a range of attitudes and behaviours regarding the existence of a supernatural being, the afterlife, meaning and purpose in life, prayer, and other markers of religion and spirituality. For example, over half of religious nones are “inactive nonbelievers,” showing no sign of religious or spiritual belief or practice, while about one-quarter consider themselves “spiritual but not religious.”

5. When examining a range of social and moral issues such as abortion, same-sex marriage, women in the workforce, the environment, government aid for the poor, and immigration policy, religious nones are more left-leaning than religious affiliates, especially in regions with higher proportions of religious nones.

6. Religious nones—atheists in particular—and evangelicals do not generally look upon one another in a positive light. Moreover, while atheists do hold many favourable views toward some religious groups such as Buddhists, Hindus, or Jews, evangelicals tend to hold predominantly negative views toward every (non)religious group outside of Christianity.

7. The vast majority of religious nones are very content with their lives and religiously unaffiliated status; they are not clamouring to turn to God or join a religious group. Strengthened preaching, music, or programs do not generally draw in religious nones. Rather, such efforts primarily help to retain those already in congregations or contribute to transfer growth from other churches.

Do these findings surprise you or affirm what you already suspected was the case? For those in local churches, what should you make of these data and possibly do (or not do) in response? I offer three invitations.

First, learn more about religious nones, turning to sound empirical data rather than well-intentioned anecdotes, opinions, or platitudes. Akin to missionaries who learn the language and values of another culture when entering new terrain, Canadian churches are in a shifting landscape that warrants careful study. I beg you, do not live in a world of narratives based on how you wish things were; understand the landscape as it is, and then proceed accordingly.

Second, meaningfully interact with religious nones in your midst and pursue bridge building activities around common interests. Sociological research reveals that our perceptions of others tend to change as a result of our interactions with them. Too often it seems that evangelical Christians in particular have misguided perceptions of religious nones because of very little interaction with those outside “the fold”—a problematic reality for those who claim to believe in the “good news.” So, are you in relationship with religious nones—family, neighbours, or coworkers, perhaps? Listen to and learn from them, on how they view and experience the world. Pay attention to common interests such as caring for the “least of these,” and consider ways to tangibly partner together.

Third, the number one reason a person joins a religious group is because someone personally invites them. Comparatively speaking, evangelicals have a better track record in this regard than other traditions. Still, few religious nones will necessarily be open to such an invitation, but research shows that some are.

I encourage you to be attentive and open to this possibility of inviting someone into a strategic and appropriate next step in their faith journey with the living God. Out of an informed posture on religious nones in Canada, and in the context of relationships that have been mutually nurtured and valued over time, where might an invitation possibly make sense?

Share:

Find more posts about:

joel.thiessen

Support the mission

The Global Advance Fund (GAF) is a pooled fund that supports our workers in Canada and around the world to share the Gospel with people who haven't yet heard the name of Jesus. Your continued generosity equips and sustains our workers and their ministry.

Joel… thanks for posting this.

Any thoughts regarding why Quebec is so low? I have understood Quebec to be regarded as possibly the most secular of our provinces, yet it shows the opposite here… am I understanding the stat correctly?

Hi Terry:

Quebec is the lowest because people continue to identify as Catholic, even if they are not particularly observant or orthodox in their views (i.e., “cultural Catholics”). You are right that Quebec (and BC) are among the most secular provinces in the nation, but they are at opposite ends of the ‘religious none’ continuum. We unpack this more in our book too (None of the Above).

I hope this helps!

Joel

Having studied and written about this phenomenon (Thoughtful Adaptations to Change: Authentic Christian Faith in Postmodern Times: Friesen Press, 2017), I applaud what Joel has written about here. The reality is… evangelicalism has lost significant ground in many ways in our culture. Being aware of this and finding ways to address this reality through an understanding of what is driving this change is an important factor in calling ourselves to prayer and diligence in seeking the Lord about how to reach out to our neighbours with the grace and truth of Christ.

That helps, thanks Joel!

If your information is coupled with something like “The Truth Project” by Focus on the Family, more Christian apologists might feel less intimidated when trying to be living witnesses to the Nones who can run “scientific” circles around us too often.

There is another aspect of non-religious identity (versus non-religious in practice).

Certain religious traditions have had a stronger cultural role that permeates even among the non-religious (even non-believers) so many continue to pursue a cultural identity of their familial “faith”. Plenty of “cultural Sikhs” or “cultural Muslims” exist in Canada (and elsewhere) in addition to RCs.

On the other hand, those coming from families practicing mainstream Protestantism, Buddhism, or Traditional Chinese religion tend to throw off any religious ‘label’ once they become non-practicing. Ex-Hindus are somewhere in-between these two extremes, but it would be interesting to see if the second-generation Canadian born children follow their ex-Buddhist and Chinese counterparts (or not).

No wonder areas with the highest percentages of WASP and East Asian (plus Vietnamese) populations tend to show the highest declared non-religious levels.

Being a member of that group, I would say that characterizing people as religious none’s is a analytical mistake. The categorization would be more useful if it was driven from a non-religious standpoint which identifies people who are religious and why that is the case. If you were an alien who landed on earth you would observe human religions as man-made concepts of which various versions have been adapted by various peoples. Why they have taken their path is the true story. I would imagine that the study of religious none’s is more of an exploration as to how and why that story has reversed in our current environment.